Barnsley Manor

- Nov 10, 2019

- 25 min read

Our adventure in researching Barnsley Manor spanned a little over 6 months. We are in the process of filming some of the highlights we discovered. Below is from our You Tube Channel and features our presentation day and our first tour. More to follow:

The History

"Barnsley Manor", as it is called today, has stood witness to over 250 years of history, including the birth of the America. The building and its grounds have housed prominent, influential and perhaps controversial families and its story is entwined with

their struggles and triumphs. The land surrounding the home has been referred to as the Growden Estate and Tatham Plantation while the mansion home at the center of this research has been called Barnsley’s Ford, Croydon Lodge, the Swift Mansion, and the Dingee Estate. Owned by only three families over its lifetime, the home has survived fire, neglect and vandalism and is now being restored to stand witness to future history.

Barnsley Manor, is situated in Bensalem Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Bensalem today encompasses 22 square miles of land framed by three waterways: the Neshaminy Creek, the Delaware River, and Poquessing Creek. Pennsylvania began as a vast expanse of land granted to William Penn by King Charles II in 1680.

Lawrence and Joseph Growden (1681 to 1685)

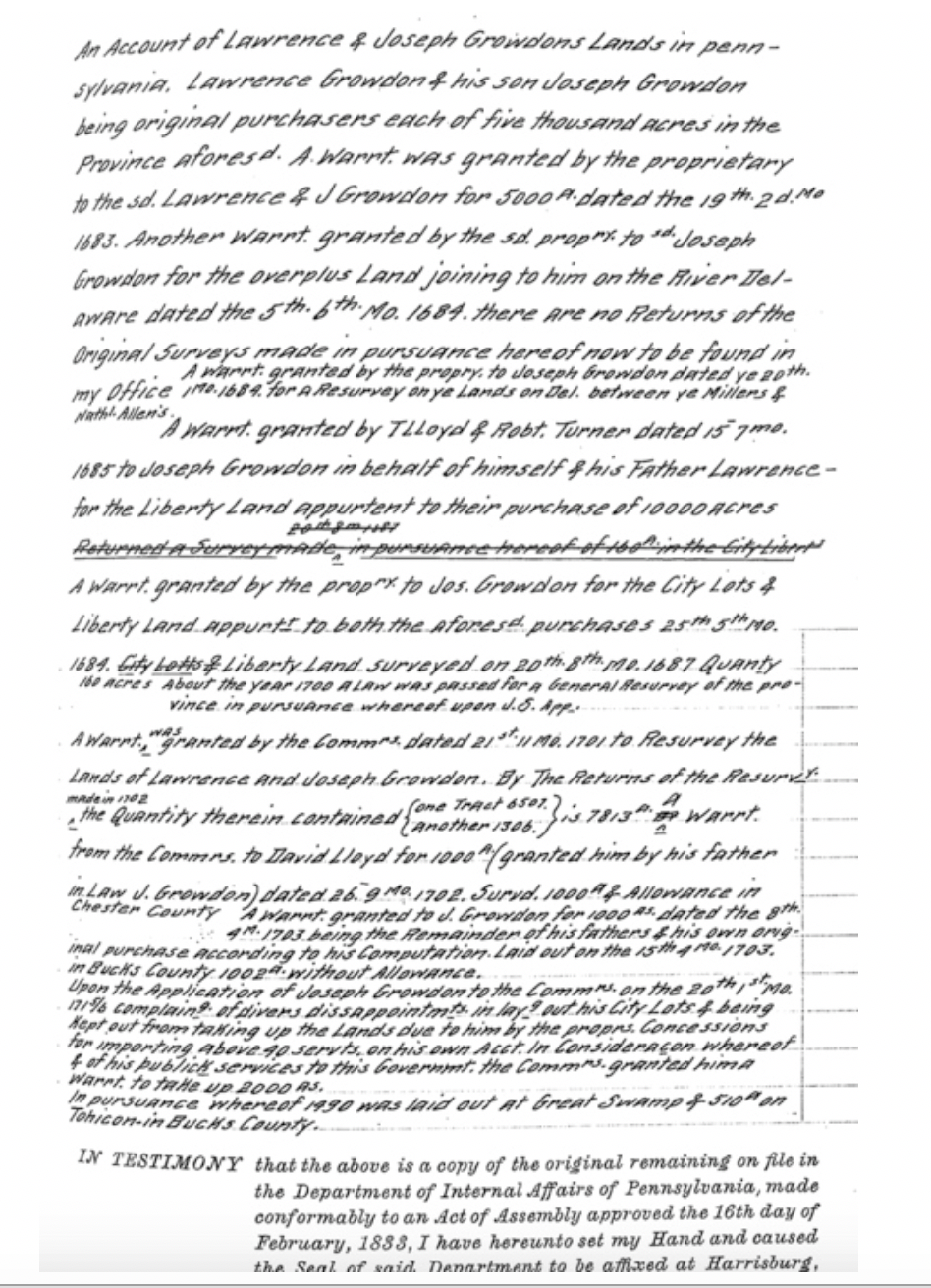

Lawrence and Joseph Growden, father and son, were wealthy pewterers in Trevose, in Cornwall, England. Each purchased 5000 acres of land from William Penn in March 1681, making them among the first landowners in Penn’s Manors. A transcription of the Growden’s land accounts is below and describes their extensive holdings in the city of Philadelphia and in Bucks County:

Lawrence Growden never made the journey to the colonies, but his son, Joseph arrived in 1683 to secure their land purchases. Joseph Growden erected the Growden Mansion not far from the site of Barnsley Manor. The land survey below show the vast acreage owned by the Growdens. Note the name of John Tatham as a neighboring landowner. This survey was conducted after Tatham purchased a portion of the Growdens’ lands in 1685. No survey prior to Tatham’s purchase is on record.

John Gray Tatham (1685 to 1703)

“a chronically troublesome Bucks County landholder”

John Gray, who went by the alias John Tatham, purchased 1000 acres of Growden’s property in 1685, the same year he arrived in the Colonies from England. He was married to a woman named Elizabeth, but not much else is known about her. John and Elizabeth had three children who survived them: John, Elizabeth and Dorothy.

John Gray was initially held in the esteem of William Penn. Penn wrote to one of his counterparts in Philadelphia in March 1685, “Pray be carefull of thy carriage to one Gray, a Rom. Cath. Gent. Yt comes over now, he is subtile & prying & lowly… but not such a bottom in other things, he is a Scholar, & avers to ye Calvanists… he comes in a post, be sure to pleas him in his lands & for distance he must take where it is clear of other pretentions.”

Aside from the land Gray purchased from the Growdens, he also secured 5000 acres directly from Penn in Chester and Bucks Counties as depicted below from the Old Rights Register for Bucks County[5].

Gray’s favor with Penn was short lived, however, by 1686 Penn had apparently discovered new information about him, writing: “Gray is a Benedictine monk of St. James’, left them and his vows, is married there, the congregation has spoke to the King about him, and to me.[6]” One wonders if the alias Tatham was an attempt at hiding a past life as a monk?

John Gray (Tatham) appears as a landowner in the earliest map of Pennsylvania as drawn by Thomas Holme in 1687. His land is depicted to the South of lands owned by Lawrence & Joseph Growden. Tatham’s influence on the boundaries of parcels in Bucks County was recounted in a lengthy article about Surveyor Thomas Holme.

The full text of the story of Gray is worth repeating here in its entirety:

“There is more definite information regarding the circumstances connected with the survey of the Charles Pickering and Company tract, known as the Mine Hole Tract, whose lines Holme ran personally in the summer of 1686 in order to thwart what may have been the first attempt at claim jumping in the history of mining in this country. The incident began with the disclosure by an Indian to Pickering that in a place beyond the Welsh Tract there were mineral deposits whose appearance seemed to indicate the presence of silver. Pickering went there to verify the information and came away satisfied of its truth, but he had failed to keep the matter a secret. Shortly thereafter, a Bucks County resident named Robert Hall sought to obtain a warrant for a survey to be run if he should succeed in finding the site of the deposits. When the Commissioners of Property refused to issue the desired warrant. Hall found a ready ally in John Gray, alias Tatham, a chronically troublesome Bucks County landholder, who held Land Office warrants available for execution. With the help of an Indian, Gray succeeded in ascertaining the location of the mine and then induced Thomas Fairman, regularly assigned to Philadelphia County as a deputy, to go beyond the limits of former surveys and lay out 1000 acres there.

On learning of the breaches of Land Office procedure thus committed by his deputy, Holme advanced proposals to Thomas Lloyd, president of the Provincial Council, for countering Gray’s action, and having obtained Lloyd’s assent, he proceeded to carry them out by going up the Schuylkill with an assistant to the northern limits of the John Pennington and Company grant. He ordered the Commissioners of Property to ‘put a stop to y' Irregular grant that was made to Charles Pickering and John Gray, alias "Jathan" (Tatham),’ declaring that his surveyor general ‘deserves to loose his office, if I am rightly informed’.

Gray Tatham’s troubles went beyond Holme and Penn. He and Joseph Growden were involved in lengthy legal battles over the property Tatham purchased from Growden. According to an account published in 1959 in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Tatham took Growden to court in 1691 in Bucks County claiming that Growden owed him a sum of money and four books that Tatham had lent to him in 1685. The case was not settled until 1699, when Growden admitted to owing the money and the books at a value of 41 pounds. Growden countered Tatham’s lawsuit with a claim that Tatham owed him for the 1000 acres of land he had purchased from him in 1685. Growden had expected 100 pounds of English goods and 100 pounds cash for the parcel, which Growden claimed had not been fully received. Tatham produced an itemized accounting of his payments of goods and cash to Growden, but the Court found that the listing had been fabricated and found on behalf of Growden.

John Gray resided in Bucks County for only a short time, as he was appointed a land agent and proprietor in West Jersey in 1688. He moved to Burlington around the same time, although his family was likely left behind in Bucks County until he was established in Burlington.

John Gray’s legal troubles were also confounded by troubles on the home front. His daughter, Dorothy was involved in a scandal that rocked the family and the province. In 1699 the Burlington Court revoked the tavern license of one Widow Elizabeth Basnett for “permitting and countenancing in her house and Illegal and Clandestine Marriage between one Robert Hickman under Custody of the Sheriff as a Suspected PIRATE”. Hickman was reportedly a member of “Kid’s Gang” from Madagascar who sailed into Cape May, New Jersey and was apprehended and taken under sheriffs’ custody in Burlington. He was apparently given the liberty to confine himself to a local tavern, where his marriage to Dorothy Tatham, John Gray's daughter, occurred. Gray Tatham died shortly after this scandal, and Dorothy was definitively cut out of his will for her “graceless & shameless Rebellion”. John’s wife, Elizabeth was pregnant with their fourth child at the time of John’s death. She died in childbirth in October 1700. The inventory of John’s estate listed 7 slaves, along with his personal estate.

The Tatham property was likely conveyed to Joseph Rodman of Flushing, Long Island, NY around 1703 after the death of John Gray Tatham and his wife Elizabeth. Joseph Rodman’s daughter Mary married a lawyer named Gilbert Hicks in April 1746. Joseph was reportedly not pleased with his daughter’s marriage as Gilbert Hicks was not of the Quaker faith. Joseph gifted Mary and Gilbert 600 acres of the former Tatham tract in Bensalem Township, reportedly as a way to send his daughter away. Interestingly, two of Mary’s sisters and her brother also married Hicks’, although their relationship to Gilbert has not been explored as part of this research.

Three transactions capture the transfer of the property between 1763 and 1768. Two deeds dated 13 January 1763 transfer 537 acres from Gilbert and Mary Hicks to James Coultas, then from James Coultas and Elizabeth his wife back to Gilbert Hicks for a sum of 3900 pounds. The nature of this transaction is not fully known, however, based on Gilbert Hicks’ loyalties and impending fall from grace, one wonders if Hicks was attempting a legal maneuver to protect his property. Five years later, a deed dated 30 January 1768[16] transfers the 537 acres from Gilbert and Mary Hicks back to James Coultas permanently for the sum of 9074 pounds. The 1768 deed refers to the 537 acres conveyed as “part of 655 acres Tatham Plantation”, showing its pedigree back to John Gray Tatham. Gilbert Hicks appears again prominently in the story of this property, as he and the future builder of our subject property were colleagues and friends.

James Coultas (1768)

James Coultas was born in England and arrived in Philadelphia before 1735, as he was married to Elizabeth Ewen in Christ Church on March 13, 1735. Coultas owned a plantation and mill in the Blockley section of Philadelphia (current day Kingsessing in West Philadelphia). The map below dated 1750 shows Coultas’ (spelled Coultis) Philadelphia property on Cobb’s Creek west of the city.

Coultas did not own the 537 acre tract of land in Bucks County for long, as he sold it just 6 months after purchasing it from Gilbert Hicks. A deed dated June 4th, 1768 conveyed the property from James and Elizabeth Coultas to Thomas Barnsley. Based on this deed, it appears Thomas Barnsley actually purchased the property in 1763, when the Hicks’ were still present. Barnsley began making installment payments to Coultas in 1763, and completed the purchase with the deed dated June 4th 1768. We know that Gilbert Hicks and Thomas Barnsley carried the moniker of Esquire, and future documents prove they were friends. It is likely, based on their occupation that they were also acquainted with James Coultas, given his official titles.

Major Thomas Barnsley (1763 or 1768 to 1772)

Although Thomas Barnsley only owned the 537 acre tract for less than 10 years, he figures most prominently in the history of the current day structure as it was constructed by Barnsley, and so the history of the building begins with him. Thomas was born in Sheffield, Yorkshire, England in 1726 to parents Jonathon and Hannah Barnsley. He was their ninth and last child. According to Barnsley’s will, he had four sisters, Mary, Sarah, Anne, and Hannah. It has been written that Thomas spent his early military years in Ireland, where he met and married, however, other accounts dispute the Irish connection based on discrepancies in dates and documents related to Barnsley.

“Flintlock pistol, fitted with brass trigger guard, lion head mask butt plate, and inlaid brass escutcheon plate on the grip.” Photo credit: American Philosophical Society

A dueling pistol in the care of the American Philosophical Museum in Philadelphia is

credited to a gunsmith named T. Hughes in Cork, Ireland (ca. 1710-1730).

The pistol was thought to be owned and used by Thomas Barnsley, perhaps lending some credence to Barnsley’s time in Ireland.

Barnsley arrived in the colonies with Lord Loudon in 1756, under whom he served as Captain of His Majesty’s Sixtieth or Royal American Regiment of Foot in the French and Indian War until 1760.

A biographical sketch prepared by William J. Bell, Jr. 1963 paints a full and colorful story of the man who built Barnsley Manor. It describes Barnsley as a prominent resident of Bucks County and well known in Philadelphia. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society, although he only attended a few meetings. It also mentions his satisfaction in voting to elect his friend and neighbor Gilbert Hicks.

Records and published accounts indicate that Thomas and Bersheba spent their earliest years in America living outside Fort Pitt. According to Bell’s sketch, Thomas’ wife joined him at Fort Pitt as soon as it was “safe.” A census of 1761 showed their “family” as four men and two women, including servants. They were living in a house outside the Fort. The following is an account given to Colonel Henry Bouquet, an officer of Fort Pitt, of the “mood” of frontier living.

Barnsley took great pleasure in his gardens at the Fort and carried on with gardening after he left his post in the Spring of 1762. He reports “our oats, Indian corn and … goes on very well and denotes a plentiful crop….except the carrots and the parsnips in the lower part of the garden, which does make much of an appearance yet.”

Colonel Henry Bouquet, mentioned in several of Thomas Barnsley’s letters, has been portrayed as being involved in a plan to deliberately infect Native Americans around Fort Pitt with small pox. Letters from the summer of 1763 between Bouquet and his commanding officer, General Jeffrey Amherst, detail the plan and agreement to provide the tribe with blankets from the small pox hospital. It appears the plan was carried out, however, it is not known exactly which British officers gave the final orders. Sadly, a small pox outbreak did occur in the Indian population around Fort Pitt in 1763. It is also not known if Thomas Barnsley was involved, or had any knowledge of the incident at Fort Pitt, although it is notable that Barnsley purchased land in Bucks County that same year and resigned from military service three years later.

Barnsley continued his military service after the French and Indian War as seen in the letters below. His disdain for liquor in military affairs is evident.

To

Capt Shelby

Fort Loudoun the 13th Sept 1764

Sir,

I received yours of the 12th Jun and must observe to you that Colonel Bouquet has not left any directions with me concerning the granting of passes, notwithstanding if the goods you mention Mr. Moran to have now at Bedford, be such as will be useful to the Army, viz., shirts, shoes, stocking, blanketing, etc, I believe it would be doing of service to the people of the Communication to take them along, and in that case he has my liberty for so doing, provided he does not take liquor of any kind either to sell or give on the road or at Fort Pitt. He must likewise produce his invoice to the commanding officer at Legionier, as also to Col Bouquet or the commanding officer at Fort Pitt. I have the honour to be Sir your most obedient humble servant,

Thomas Barnsley D.L.M.G

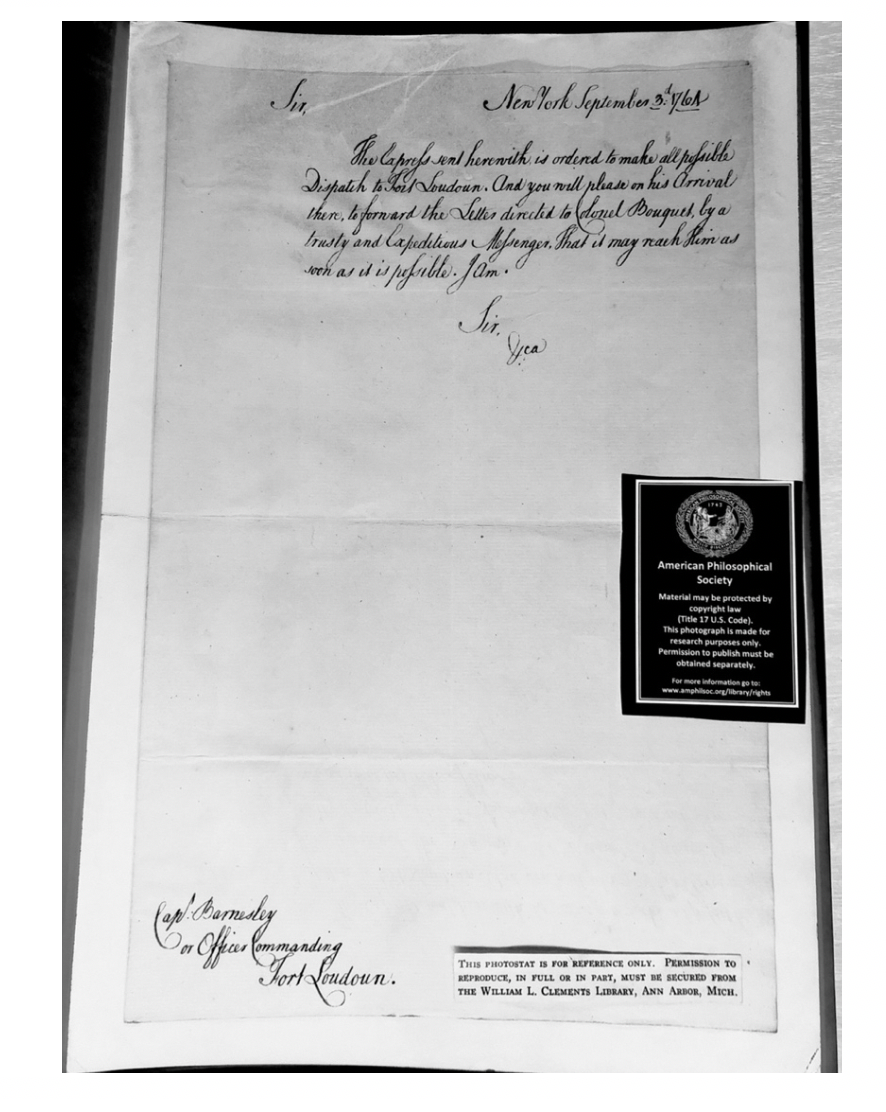

A letter written by Barnsley on behalf of Lord Loudoun resides in the archives of the American Philosophical Society:

Transcribed as:

New York, September 3rd, 1764

Sir,

The Carpels sent herewith is ordered to make all possible dispatch to Fort Loudoun. And you will please on his arrival then, forward the letter directed to Colonel Bouquet by a trusty and expedious messenger. That it may reach him as soon as it is possible. I am”

Captain Barnsley an Officer Commanding Fort Loudoun

Thomas and Bersheba settled in Bucks County after his military career. Thomas purchased 537 acres of the former Tatham Plantation from James Coultas in 1763 and constructed a grand house with bricks that were reportedly imported from England (some accounts note the bricks were used as ballast in ships docking in the Delaware River). Bell’s Sketch describes Barnsley as humane man gifted with a sense of humor. After purchasing and building his estate, he was appointed justice of the peace by the Governor. Colonel Bouquet told the proprietor Thomas Penn that Barnsley “is not a little proud of the honors reserved for him and raises his ambitions to the Wig Party.”

Thomas and Bersheba did not have any children of their own. 1n 1766 Barnsley returned to England to resign his commission and visit family in Yorkshire. In 1767, he returned with three nephews and a niece, children of his sisters: William Smith, Jemima Shepherd, Robert Shepherd, Jr and John Stainforth. Although they were not youngsters, Barnsley was responsible for their well-being and properly preparing them for life in a new land. John Stainforth, son of his sister Ann took his name and carried on the Barnsley legacy.

A full description of the home and its contents are provided in forthcoming pages of this narrative. A local history paper called “The Bristol Pike”, authored by Rev. S. F. Hotchkin and published in 1893 describes the mansion house:

“This ancient and dignified brick mansion reminds one of the colonial houses of Virginia and Maryland. The place lies at the corner of Upper Newportville and Doylestown roads. The ceilings of the mansion are high, and the old woodwork of the cornices, and around the chimney fire-places is primitive, while a marble mantel has apparently been added in the parlor. The hall is one of the finest I have ever seen. The three-cornered closets are noticeable. Every room has its special fireplace. The rooms are well lighted with an abundance of windows. The stairway of the hall is remarkably fine. A wooden arch divides the hall. Some ancient blue tiling around an upper fire-place is striking. A very peculiar lock fastens the door of the same room. The rear porch is a picturesque feature. The kitchen is indeed an antique. A fine wooden mantel surmounts the fire-place, and a crane hangs in it, as an ancient ornament. The roof of the house rises from the four corners, and is pointed at the top. The ivy that clothes the dwelling with its green mantle vivifies the old wall. Washington is said to have spent a night in the fine old mansion”.

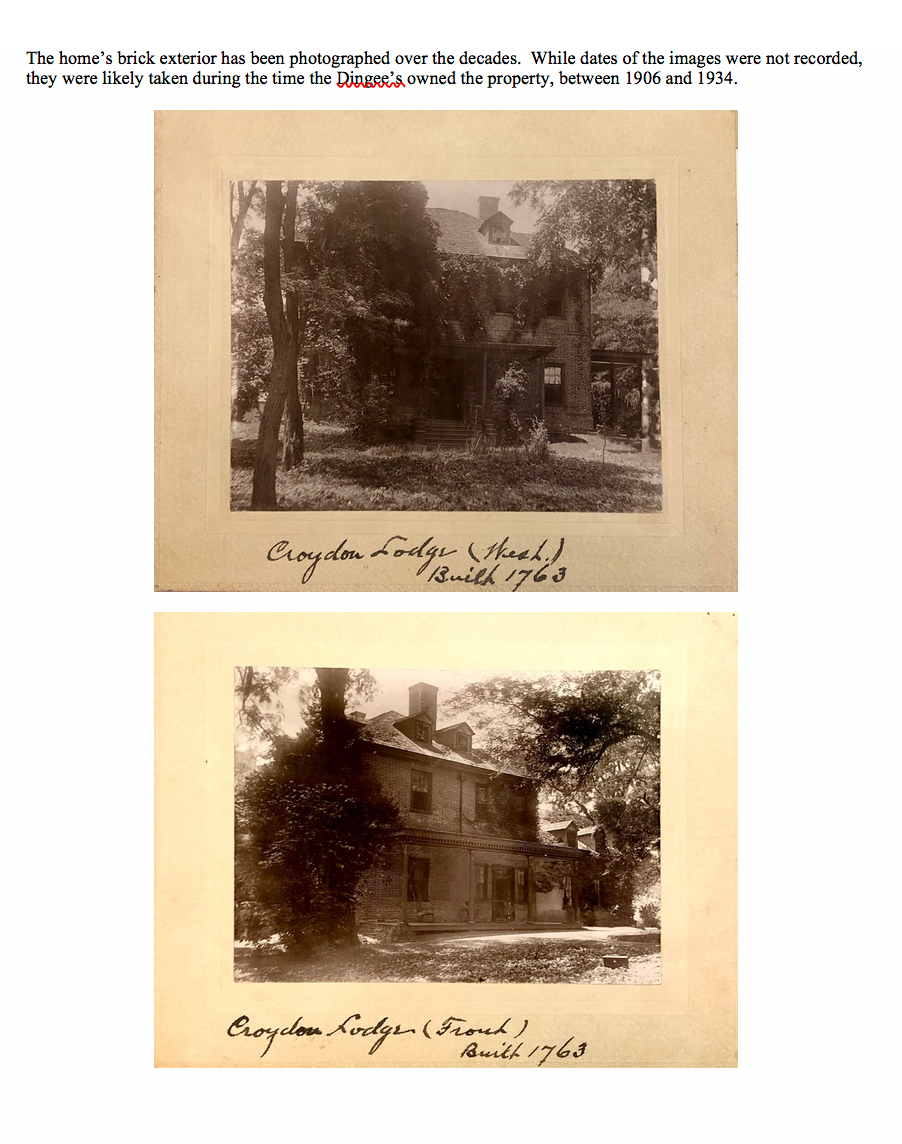

Barnsley’s estate is commonly referred to as “Croydon Lodge”, purportedly named after the place where Barnsley was born in England. However, none of the records associated with Barnsley or his property refer to the name Croydon. More on the origin of the Croydon name later.

By May 23, 1770, Barnsley had resigned his military offices and took no other part in public affairs. It is suspected that the building, furnishing and care for his new estate took priority. It appears that Thomas quickly established a grand estate in Bensalem, complete with all of the possessions one would expect of a manor home. He reportedly “preferred wearing a scarlet coat, buff breeches, gold knee buckles, a cocked hat and dress sword – traditional dress of a retired Royal officer”. Captain Barnsley and his wife attended St. James Angelican church in Bristol. They kept a hospitable house and table and Thomas liked to play the Squire. The area around his plantation became known as “Barnsley’s Ford.”

Thomas’ time on his grand estate was decidedly short, as he died in November 1771.

MAJOR FIND

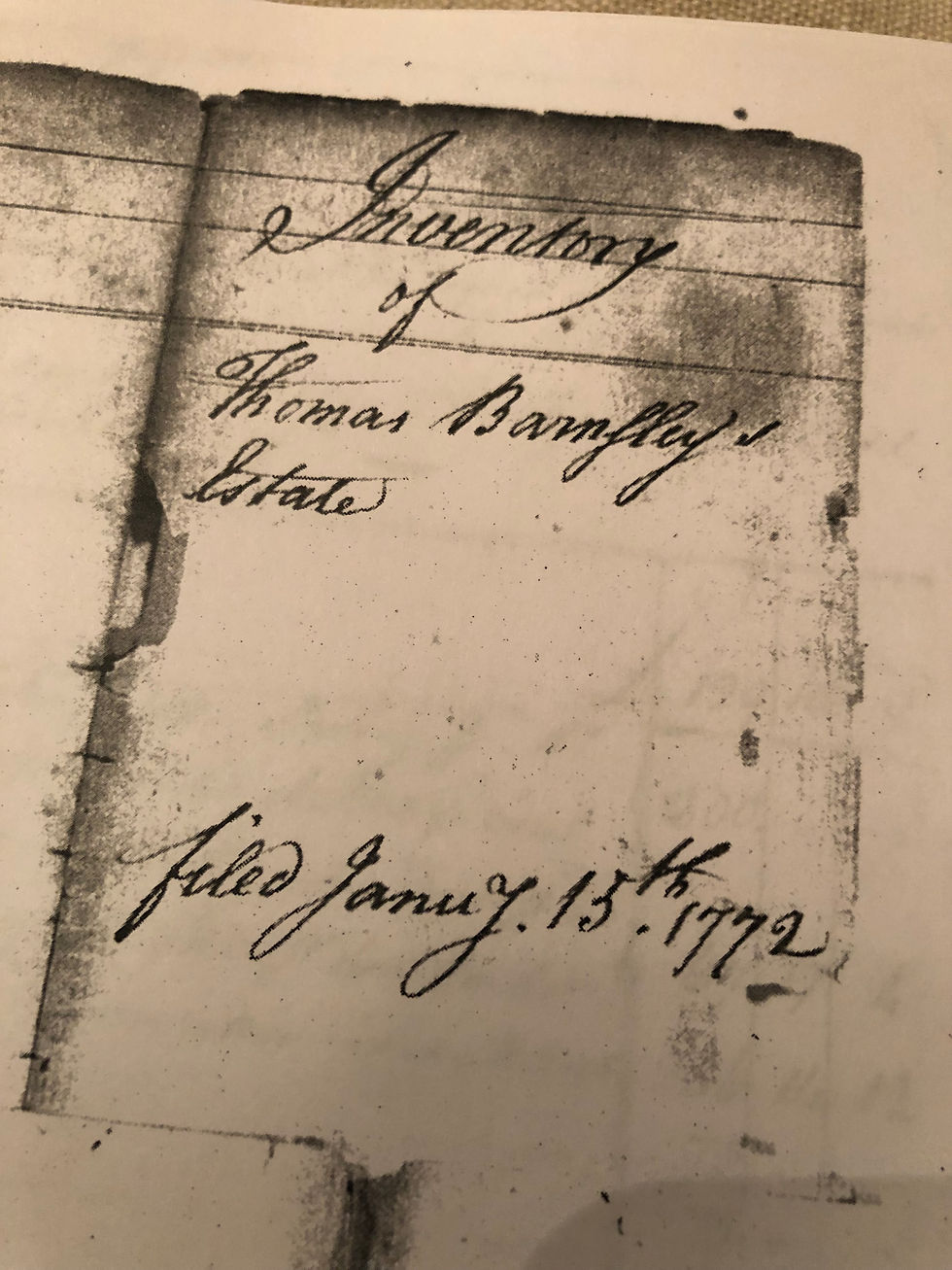

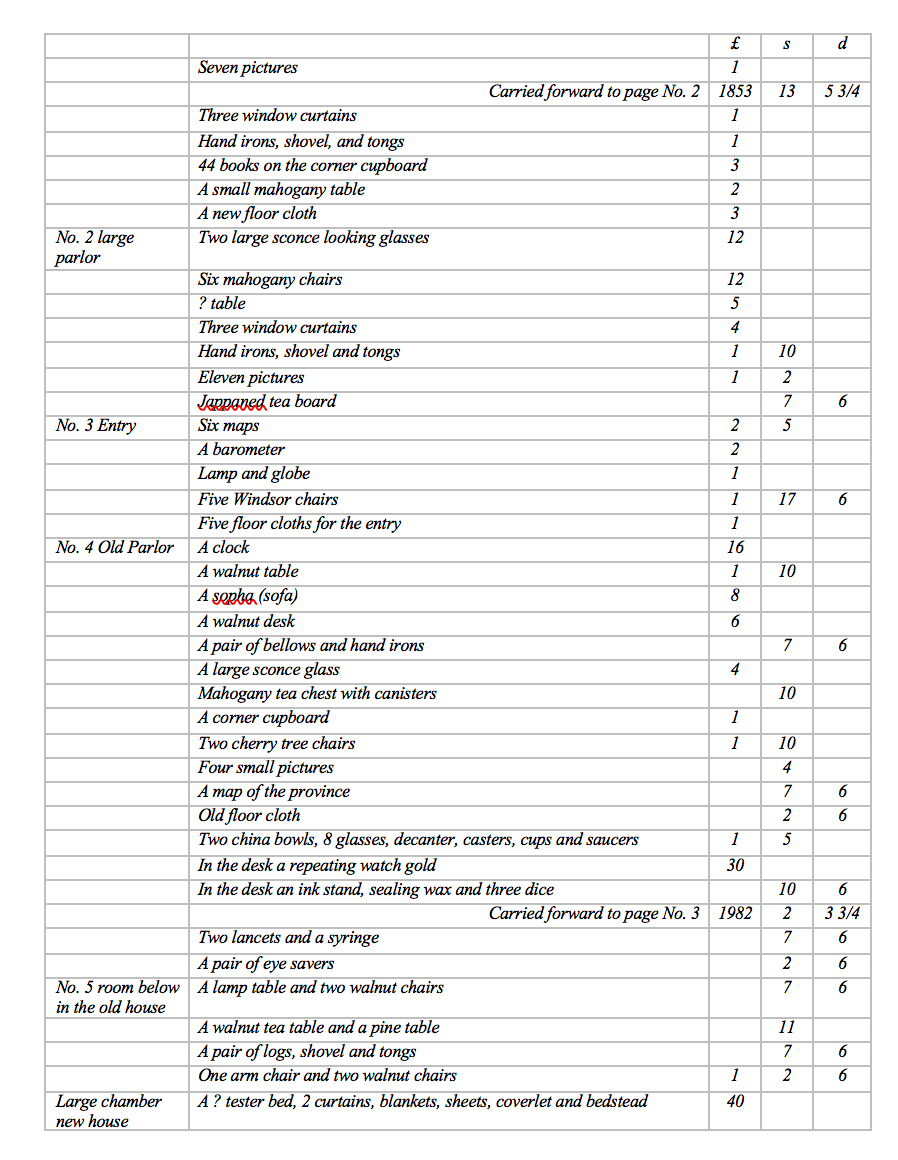

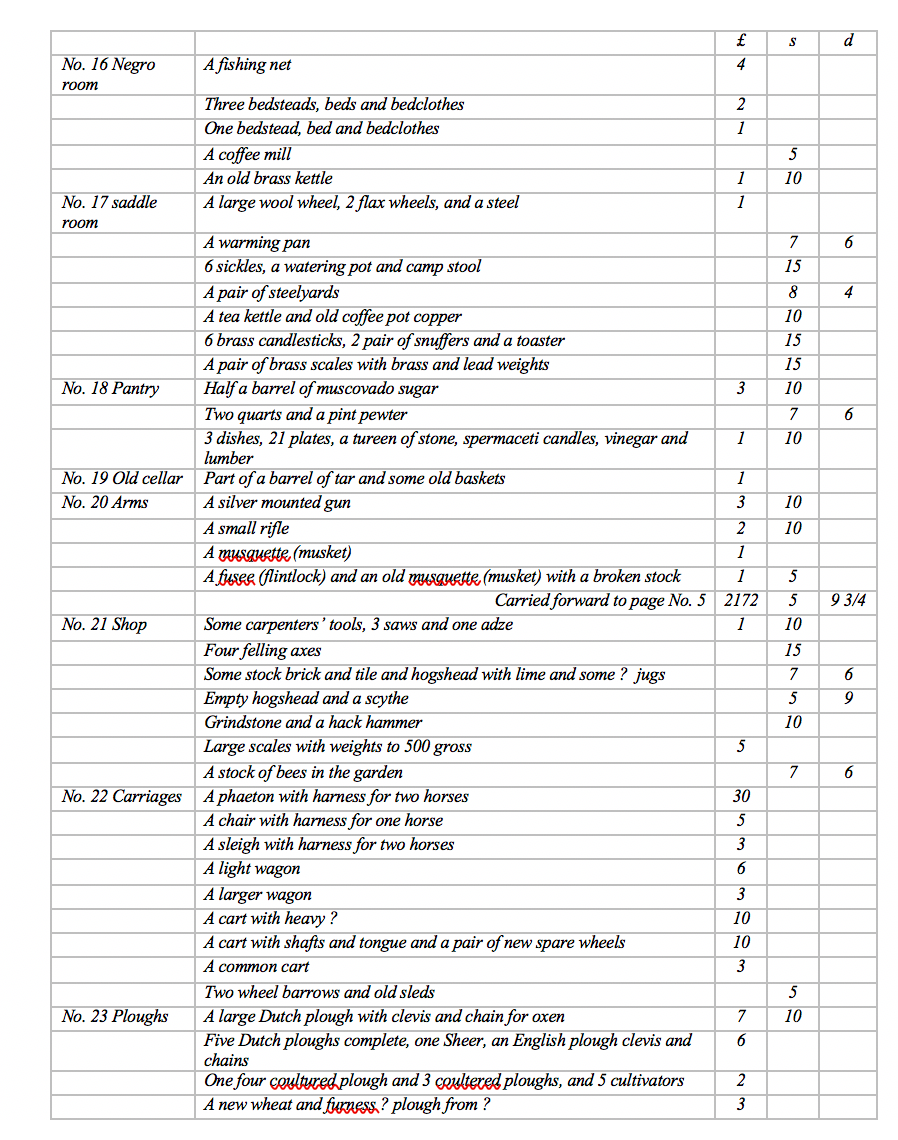

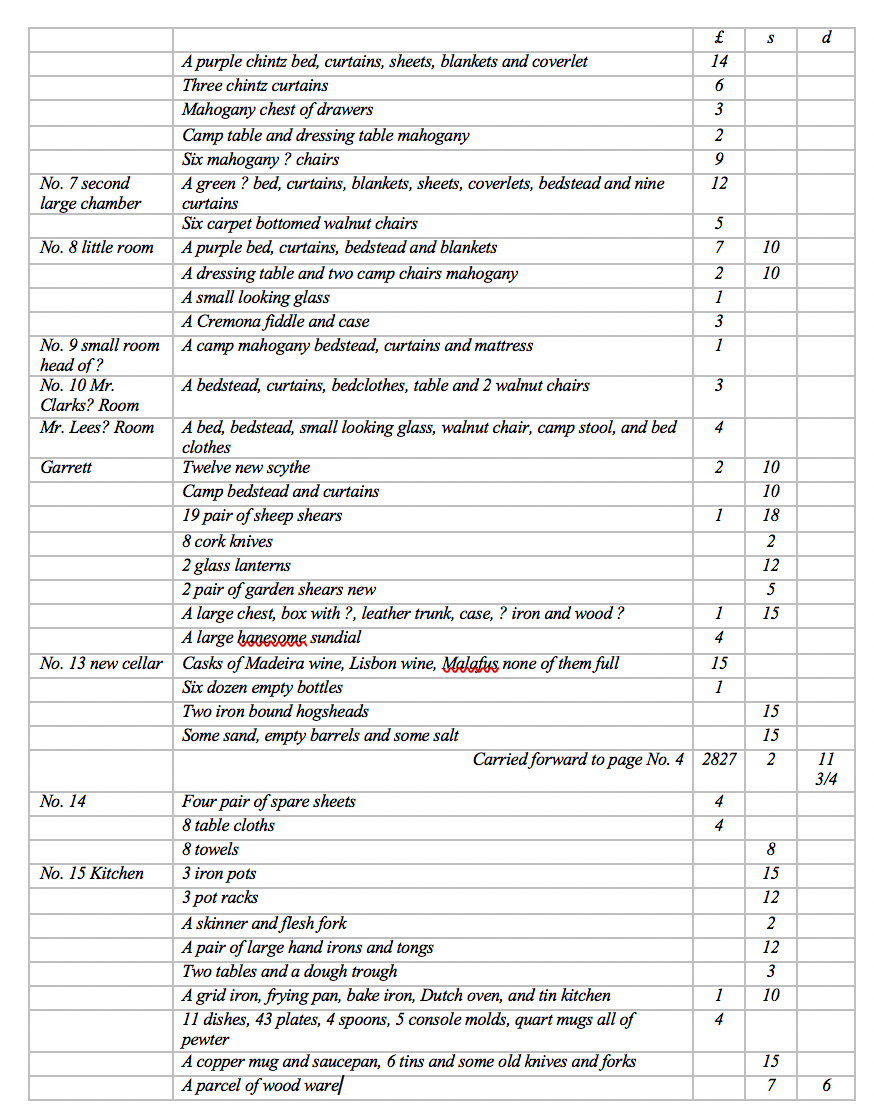

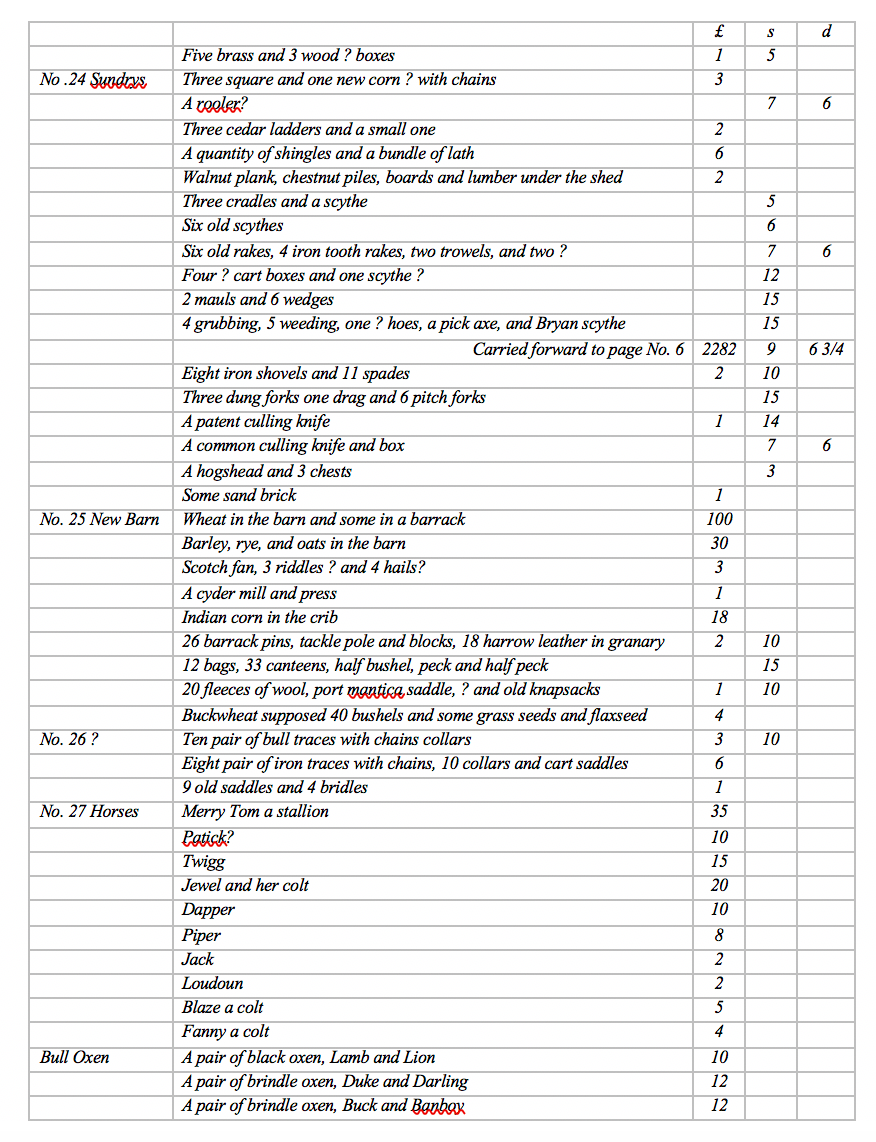

We were thrilled to be able to find the will of Thomas Barnsley!! His will details to entire contents of Barnsley Manor, including the names of the rooms and contains within. We have transcribed the inventory of his will below:

The inventory is detailed and provides the reader with a means to imagine the personal possessions of Thomas Barnsley arranged in each room described. Notable items include “a map of the province” in the Old Parlor, which could have been Thomas Holme’s map of Philadelphia, Bucks and Chester Counties; a horse named Loudoun, perhaps named for the man responsible for Thomas’ military career; and the listing of slaves and the items in their room.

The estate of Thomas Barnsley was advertised for sale in December 1771 and again in September 1772. The newspaper advertisements on the proceeding pages describe the buildings that were on the property in 1771 to the dimension. One can imagine that liquidating a large estate at the height of the American Revolution in the heart of military maneuvers in Bucks County would have been a difficult task.

The Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) · 9 Sep 1772, Wed · Page 4

A Public Sale was held on 5 October 1772 and the Barnsley estate was sold to John Swift, Esq for 3955 pounds. The remainder of his personal belongings, including his stallion Merry Tom advertised in April 1773.

The deed conveying the property to John Swift, Esq. is dated December 15th, 1772. The property is described as containing 537 acres, however a survey made by John Clark showed the property to encompass 560 acres.

A Note Regarding John Barnsley

Written accounts note that John Barnsley, Thomas’ nephew, inherited a fourth of the estate, and that the inheritance, paid in English currency, was not invested and became worthless after the War. However, no documentation supporting this account was discovered as part of this research. John moved to Newtown and built a very fine manor home similar to Barnsley Manor. The Newtown Historical Society provided a photo of John Barnsley’s residence. John Barnsley became a very prominent figure in Newtown. The family grew from Newtown and descendants spread to towns such as Huntington Valley and Hartsville. Image below courtesy of the Newtown Historical Society.

John Barnsley’s home present day

The Swift Family (1772 to 1883)

The home that Barnsley built was occupied for the next 101 years by the Swift family, beginning with John Swift, Esquire of Philadelphia. John was born in Bristol, England and emigrated to America in 1737. His family resided in Croydon in County Surry. The Barnsley estate almost certainly took on the name “Croydon Lodge” during the ownership of the Swift Family.

John Swift engaged in business pursuits with his uncle in Philadelphia and became a prominent figure in society and politics. He was elected as a member of Philadelphia Common Council and 1757 and was appointed as a Collector at the Port of Philadelphia by the English Government prior to the Revolution[31]. His role as Collector positioned Swift as the gatekeeper to the City of Philadelphia, no cargo could be landed at the ports without the payment of the proper duties. Enterprising agents reportedly presented forged documents and on occasion, resorted to piracy to avoid payment.

John’s first wife was Magdalene Kollock McCall, the daughter of Jacob Kollock and widow of Jasper McCall. John and Magdalene were married at Christ Church in Philadelphia in May 1749. The couple welcomed the following children to their union:

John White Swift (30 January 1749/50 to 1818)

Alice Swift (20 Feb 1750/51), married first Robert Cambridge at Croydon Lodge on 22 November 1778, second James Crauford

Joseph Swift (9 February 1752 to 1810)

Charles Swift (26 August 1757 to 8 October 1813)

After Magdalene’s death, John Swift married her niece Rebecca Kollock. John’s purchase of the Barnsley property in 1772 places his children listed above as adults at the time their father moved to Bensalem. John is said to have spent his “later years” at Croydon, and this account is substantiated with the documents associated with the Bensalem property. John Swift is found in records of the Bucks County Office of the Prothonotary with two female slaves registered in 1789, Juliana and Belinda. John’s occupation is listed as “gentleman”.

Charles Swift, youngest son of John and Magdalene was admitted to the Philadelphia Bar in 1779, and was the Register of Wills for Philadelphia County from 1800 to 1809. He married Mary Riche, daughter of Thomas Riche, Esq. on 31 December 1783. Charles and Mary Riche had the following children:

Thomas

Magdalen Peel (1785 to 1859)

Sarah

Charles (changed his name from Charles Swift to Charles Riche in 1810) m. Sarah Coombe Inman

Mary (1788 to 1795)

John (1790 to unk): admitted to the Philadelphia Bar in 1811, served in the company of “Washington Guards” during the War of 1812, and was Mayor of Philadelphia from 1832 to 1841 and again from 1845 to 1849.

Mary Riche Swift died just seventeen days after John’s birth (7 February 1790). Charles’ second wife was Mary Badger Inman, daughter of Bernard and Susanna (Riche) Badger. Mary was the widow of Captain George Inman of the British Army. She was a founder of the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts in 1803. Charles and Mary Badger Swift had one son, Lewis Swift, who was born in 1800.

Lewis Swift married Catherine Rogers Swift in 1825 and they moved to Croydon Lodge. The following children were born to them:

Mary Loret Swift (unk to 1869)

Robert Henry Swift (unk to 1881)

Catherine Swift (1833 to 1877)

Lewis Swift was a Justice of the Peace for Bucks County from 1833 to 1850[35]. According to a family history, Lewis “lost one eye in 1840 as a result of a horse’s kick and, a few years later the other eye becoming infected, he lost that too, and for the last twenty years of his life was totally blind”[36]. Mary Badger Swift died at Croydon Lodge 7 April 1833, the same year of her youngest child’s birth. The children of Lewis and Catherine Swift never married and all three died at Croydon Lodge.

Lewis and his family were enumerated in the 1860 Census[37] with a property value of $11,000 and a personal property value of $600.

It appears that Croydon Lodge was passed down from John Swift to his son Charles, who passed it to his son Lewis, who passed it to his son Robert Henry Swift.

The 1870 Census shows Robert as the head of the household at age 26. Note that Lambert Valentine, who was apprenticing for the Swifts in 1860 stayed on as a farm laborer working for Robert.

The map below shows the Swift property in 1876.

Robert Henry Swift died 5 October 1881. His will dated 15 March 1871 named George Inman Riche as his Executor. George was the son of Charles Swift Riche and Sarah Coombe Inman, a half cousin to Robert. George was also the Principal of Philadelphia Central High School.

Robert’s Will directed that interest in his estate should be divided between his sister Catherine Swift, his cousins Sarah C. Montgomery, Rosina M. Hildeburn and George I. Riche, and his uncle Charles S. Riche. Robert’s uncle Charles S. Riche died in 1877 prior to Robert’s death.

The surviving devisees of Robert’s Will apparently did not have an interest in Croydon Lodge, and the property was put up for public sale at the Delaware House in the City of Bristol. An article in Philadelphia Inquirer[40] (below), dated November 12, 1881 advertises the sale.

Richard Dingee (1883 to 1911)

Richard Dingee was born in Philadelphia on January 11, 1829 to Obediah Dingee and Hannah Welch. He had a brother named William. The family later relocated to Lancaster County.

Sallie B. Dingee, wife of Richard Dingee, Doctor of Medicine, purchased Croydon Lodge via a deed dated 5 May 1883 for $13,370.

According to our research, Dr. Dingee is responsible for making most of the improvements at Barnsley Manor. The Bucks County Gazette featured a short note regarding the renovations on 29 Mar 1883. The property is described as “the Swift Mansion House.”

Richard and his wife Sallie lived in the home through the late 1800s. A Map of Bensalem dated 1891 illustrates Dr. Richard Dingee’s property totaling 107 acres. Three structures are also noted on the map.

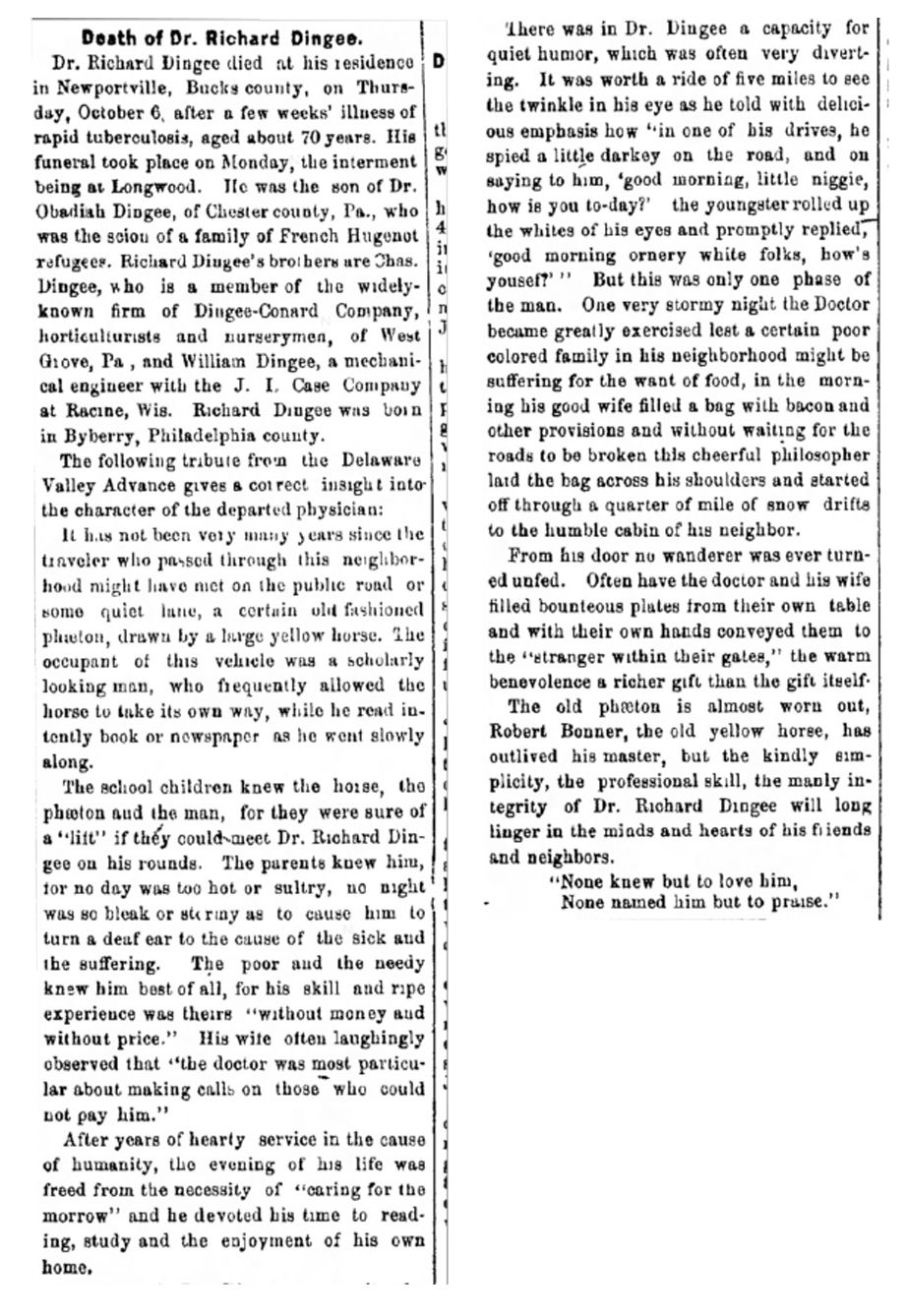

Dr. Dingee was a prominent physician in the area until his death on October 6, 1898. His obituary from the Bucks County Gazette describes his dedication to the sick and suffering. It notes he made house calls in his phaeton (one horse carriage), to visit the infirm who were too ill to come to him. He took great pride in visiting those that could not pay him and he often traded medical services for food or chickens. One can’t help but smile and compare Dr. Dingee to Dr. Baker from the television show “Little House on the Prairie”. Small town doctors are a rare breed and Dr. Dingee was a loved and respected man in his community. Bucks County Gazette, 13 October 1898.

Sallie Bailey Dingee continued to live in the home after her husband’s death. The Daily Republican captured the news of a fire in the home in an article dated December 30th 1906. The scars of a significant fire can be seen today in the walls of an upper bedroom and more specifically around the room’s fireplace. It is likely the damage was a result of the fire in 1906. The article states the mansion was destroyed, and other sources consulted as part of this research stated the home was burnt to the ground. We know, however, that many of the architectural features noted in descriptions of the home prior to the fire exist today, and the article also states that the content of the building were saved, indicating the fire was likely slow moving. The article also notes the home was owned by Dr. William Dingee, which we know is also incorrect.

A description of the property provided earlier in this narrative from the “The Bristol Pike.” (Hotchkin, S. F. 1893, pp. 348–350) provides a detailed description of several architectural features of the house, including “…the old woodwork of the cornices, and around the chimney fire-places is primitive, while a marble mantel has apparently been added in the parlor. The hall is one of the finest I have ever seen. The three-cornered closets are noticeable. … The stairway of the hall is remarkably fine. A wooden arch divides the hall. Some ancient blue tiling around an upper fire-place is striking."

These features either exist in the home today (the arch in the entry hall and corner cabinets) or were intact as recently as 2004 when photographs of the building’s interior were taken (the blue tile around an upstairs fireplace), lending credence to the opinion of these researchers that the building was not completely destroyed in the 1906 fire. Further proof that not everything written in newspapers articles or history books is accurate!

Marble Fireplace in front lower left room; no longer present

Photo on right is blue ornate tile said to be of Dutch influence and replica of those found at the Betsy Ross house in Philadelphia. Photos of courtesy of Bensalem Historic Society - 2004

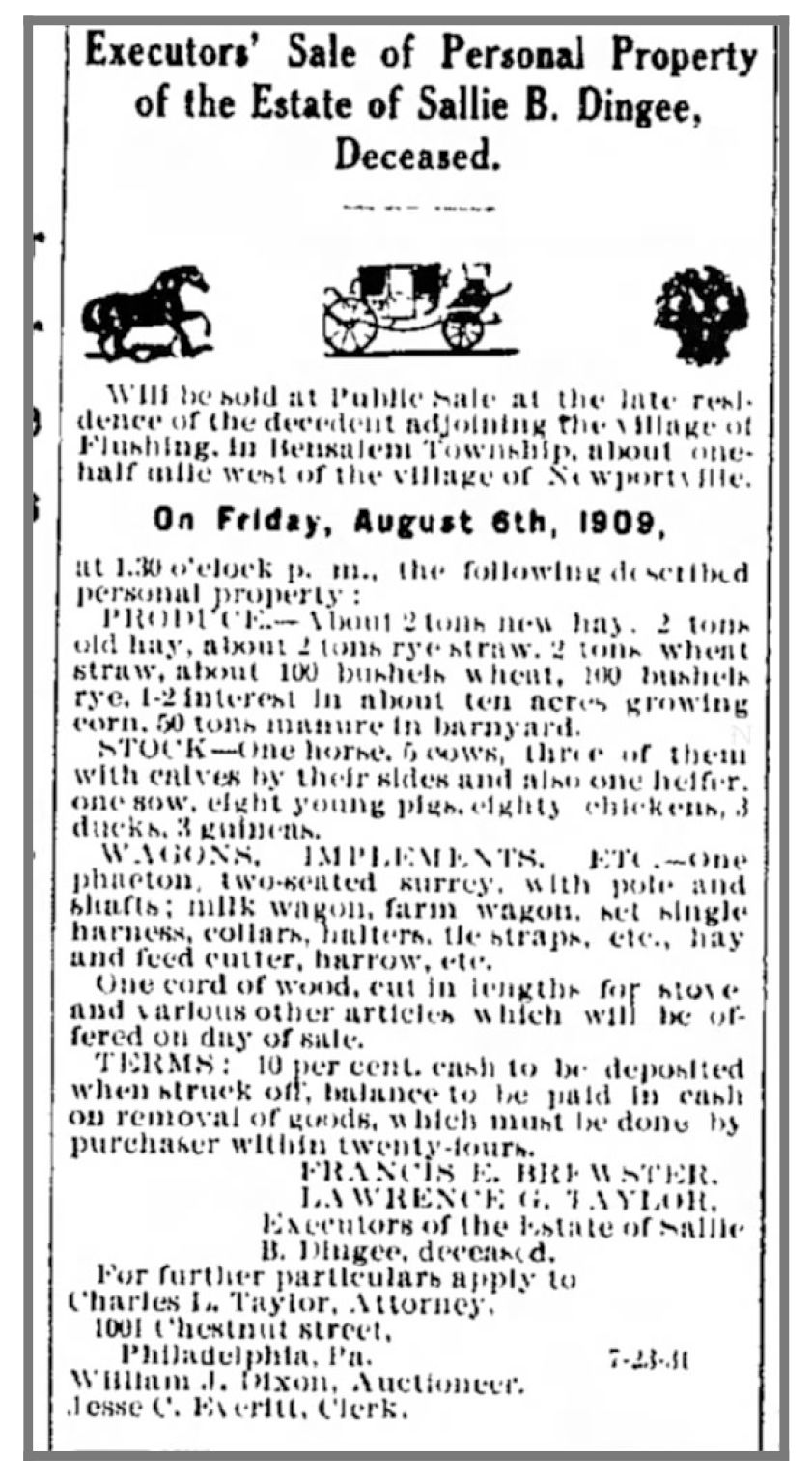

Sallie Bailey Dingee remained a widow until the time of her death, July 4th 1909. She was 83 years old. The division of her estate was detailed in a complex will. Sallie ordered that the house and land be held in trust for 10 years, after which time the estate was to be sold at public sale if the proceeds benefited her heirs. If the property was sold the proceeds were to be divided among Sallie D. Bailey, Dr. George S. Bailey, Charles Bailey, Eliza L. Frost and her executor Laurence G. Taylor.

An article in The Bucks County Gazette dated 30 Jul 1909 details the public sale of Sallie’s personal belongings, including her late husband’s Phaeton, a horse drawn carriage that he used for transportation when he was a doctor.

A survey was drawn as part of the probate proceedings for Sallie Bailey Dingee’s will. The survey (below) shows the location of the house and outbuildings on the property in the early part of the 1900s.

Sallie carefully considered to whom she entrusted her mansion and grounds, and even made provisions considering the then current state of the real estate market. However, the settlement of her estate was hampered by a series of events that she could not have foreseen, and the home and property fell into a prolonged state of neglect as a result. After Sallie’s death in 1909, her niece Eliza L. Frost married a man named Douglas Stewart. Eliza and Douglas had Sallie’s sister, Maggie (age 67), declared incompetent in 1910. Maggie’s illness in 1910 is not fully known, however, she died in 1923 as a resident of the Pennsylvania Hospital Department for Mental and Nervous Disorders. Eliza and Douglas then conveyed their interest in the property to Sallie D. Bailey in 1911, as instructed in Sallie B. Dingee’s will.

Sallie Dingee Bailey (1911 to 1942)

Sallie Dingee Bailey was born August 5th, 1868 to parents Samuel Bailey and Mary Goldsmith. Samuel Bailey was a brother to Sallie Bailey Dingee. It is not clear from where Sallie (the younger’s) middle name of Dingee was derived. She was born in 1868 before her Aunt’s marriage to Richard Dingee (1881) and a search of her parents’ lineage did not reveal an immediate alternate connection to the Dingee family. Photos courtesy of the Miller family.

Sallie Bailey was 43 years old when she took possession of her Aunt’s estate in 1911. Little more is known about Sallie Bailey’s time on the property, however, it does appear the estate was tied up in legal battles.

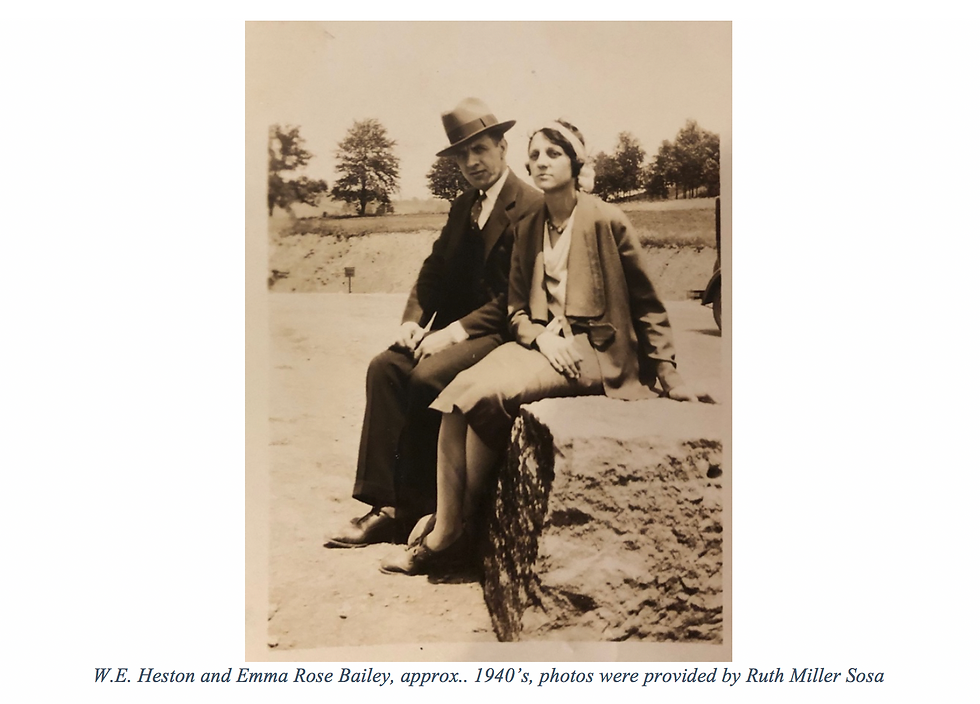

Sallie Bailey assigned her life interest in the property to W.E. Heston Bailey (also known as Ellwood Heston Bailey) on March 4th, 1942. This transfer was in line with the wishes of Sallie Dingee, and fulfilled the succession of ownership documented in Dingee’s will. Sallie Bailey died just three years later on February 13, 1945, at the age of 77.

W.E. Heston Bailey (1942 to 1992)

William Ellwood (W.E.) Heston Bailey was born in August 3rd, 1899 in Philadelphia to George and Edith Bailey. His father George Bailey was the nephew of Sallie Dingee.

The photo below is a family portrait of George’s children: Whitton (standing), W.E. Heston (baby), Edith (middle) and Elsie circa 1899. Also born into this family were Norris and Sallie (not pictured.) The eldest child, Whitton (standing in the photo) passed away at age ten in 1904. According to family members his sister Elsie never recovered from the trauma of his passing.

W.E. served in the Marines in World War I, his registration card is pictured at left. He was stationed in Paris Island, Norfolk VA and Julien Creek. He enlisted in 1917 at 18 years of age and completed his service two years later, listed in “excellent condition.”

W.E. married Emma Rose Wells, they had two daughters Ruth and Elva.

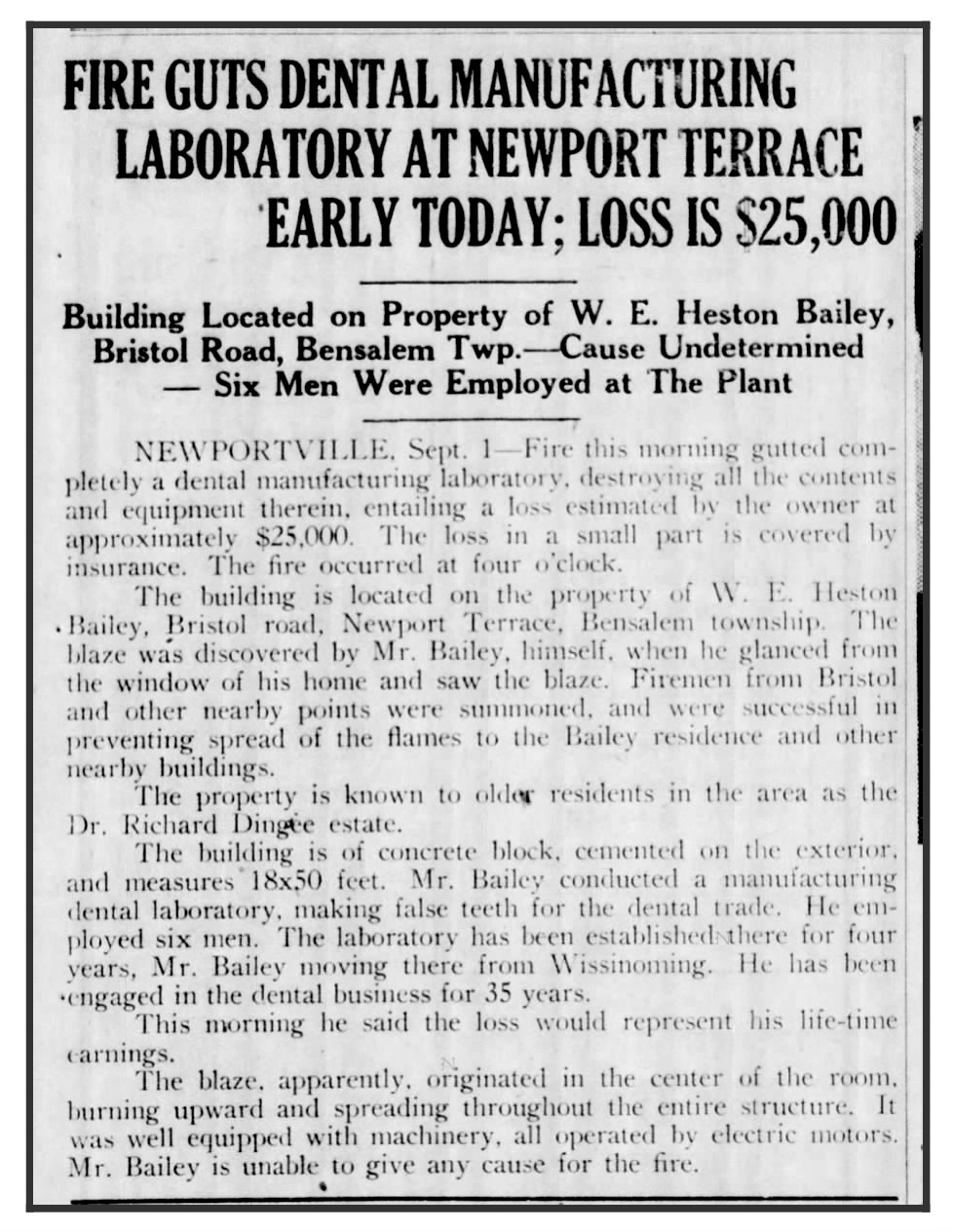

W.E. Bailey apprenticed with his father, George Bailey as a dental laboratory technician after serving in the Marines in World War I. In 1923, W.E. opened his own business, Bailey Dental Laboratory. After moving to the former Dingee estate, he operated his dental laboratory out of a block building on the grounds of the mansion house. Plaster dental molds can still be found on the property. A very curious thing to find if the one does not understand the history of the property!

In 1949, fire once again touched the property. The article below describes a conflagration that completely destroyed Bailey’s laboratory, with damages amounting to his life savings.

W.E. and Emma Bailey’s daughters Ruth and Elva raised their families in the large home.

Ruth Bailey married Norval Miller on July 28,1945. Their wedding photo (above) was taken on the grounds of Barnsley Manor.

Various Bailey/Jackson family photos taken in and around Barnsley Manor. Dates are approximately 1960’s – 1970’s.

Rich Miller was another contact we made. Rich was the first born to Ruth and Norval. He is Ruth’s sister and also grew up at Barnsley Manor. Rich was gracious enough to meet us twice and provided his own set of family pictures.

The captions are directly from Rich Miller and describe his time growing up at Barnsley Manor. We are incredibly grateful to the Miller/Sosa families for sharing their family photos with us!

“This is the downstairs kitchen, the main one used by the Baileys and Jacksons. The Millers had their own smaller kitchen up on the second floor ....”

Christmas at Barnsley

“Pictured on right is Elva and John Jackson. Estimated time is early 2000's. Pictured on the right is the main downstairs dining room decorated for Christmas. This dining room was used mainly for holidays like Christmas and Thanksgiving, and the whole family got together there, including Grandmom and Granddad Bailey. As the original kids grew and had kids of their own, card tables were added to expand the capacity. There were times when we had 16 or more people there. Sometimes young couples alternated between his and her families, so not everybody was always there as the kids married and the family got larger. Holidays were very beautiful in that old house!”

A collection of exterior images from the time the Bailey/Miller families lived at the home.

Holland Enterprises, Inc. (1992 to 2015)

Holland Enterprises, a builder, purchased the property in 1992. It was in a state of disrepair. The builder had plans to build new homes on the property but died before his plans could be put into place. Fire touched the mansion once again in the Spring of 2013. Sadly, this time it was intentionally set. The article below describes the arson damage and subsequent criminal charges.

Habitat for Humanity purchased the property in 2015 until the the current owners purchased the property in 2017. It is currently being restored to its former glory.

It all started with Facebook.....

The Granddaughter of the Miller's saw a post on Facebook from the current owners of Barnsley Manor. We contacted her and were introduced to her aunt, who also called Barnsley Manor home. We were graciously invited to her home and shown a huge collection of family photos, some featured here. We sat for hours and smiled as we heard tales of growing up in the big house with her siblings and cousins. The grand hall hosted many, many gatherings, from family dinners, wedding and even funerals. Some of our favorite photos in her collection were of her growing up at Barnsley Manor, but mostly her wedding!

"Barnsley Manor" has stood witness to over 250 years of history, including the birth of the America. The building and its grounds have housed prominent, influential and perhaps controversial families and its story is entwined with their struggles and triumphs. It has been owned by only three families over its lifetime and has survived fire, neglect and vandalism. We are so thankful this amazing piece of history is now being restored. The current owners stumbled upon Barnsley one day on their travels. Did they find Barnsley or did Barnsley find them? We believe that perhaps historic homes have a way of picking their stewards. We are so happy that this home will stand witness to future history.

We want to thank all who helped us along the way with this project. The Bensalem Historic Society, The Newtown Historic Society, The Mercer Museum and Spruance library, the Miller and Sosa families and especially the owners of Barnsley Manor. We had such a great time uncovering Barnsley's story.

More images from our research files:

©2019 History Attic Research, LLC – all rights reserved

Printed in the United States

This narrative was created based on property deeds, published histories, maps, and family genealogy sources. The information is accurate per the authors’ understanding and interpretation of the source material. No duplication or copying is permitted without History Attic Research's permission. This a summary of our findings, a full copy is available upon request. Deeds and supplementary documents are given to our clients. Source list also available upon request.

Excellent breakdown! Programs like First Time Home Buyer Texas are helping more Texans step into homeownership, even in competitive markets. Add in an FHA Loan Texas, and buyers gain access to affordable terms without needing perfect credit or a large down payment. We also offer commercial real estate loans like Hard Money Loan Texas and DSCR Loan Texas.

This was an amazing read. Congrats on the detailed research. What exactly happened between the point of Rich Miller's photos and the 2013 arson? Rich's photos appear to be from at least the 1990's, and you mention some of them are from the early 2000's. But you also mention a developer purchased the land in 1992.

Is that to say the family lived on the property, but they did not own the land? When and why did the family vacate the property?